Julio Romero de Torres (1874-1930)

Julio Romero de Torres (1874-1930) was the son of Rafael Romero Barros, a painter and curator of what was then called the Museum of Painting in Cordoba.

He would be marked by family life which revolved around his father’s studio, the classrooms of the School of Fine Arts and Music Conservatory and the galleries of the museum, located in the same grounds as the family home.

This indisputably conditioned his future and was the backdrop to his first steps as a painter.

At the age of ten he began studying music and painting and was only fourteen and fifteen when he received prizes in the competitions organised by the Provincial School and the Athenaeum.

He carried on studying painting and, like his siblings, was deeply influenced by his father’s teachings.

As he became increasingly involved in the cultural scene of Cordoba and closer to that of Madrid, his life continued to be underpinned by two fundamental pillars: his family and painting.

In 1895 he secured his first artistic success with Look How Pretty She Was! ,which was also his first success in Madrid.

But 1899 would be one of the most important years in his life, as he married Francisca Pellicer and was granted an ancillary post at the Provincial School of Fine Arts, where he finally became a lecturer in colour, drawing and copying after the antique and from live models.

He continued his teaching career years later in Madrid as a lecturer in ancient drawing and drapery at the Special School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving.

During the turn of the century he was connected with the academy, the Athenaeum and the Cordoba Economic Society of Friends of the Country and attended literary and artistic gatherings.

He was involved in restoring the coffered ceilings of Cordoba Mosque and returned to these conservation tasks carried out on Cordoba’s rich heritage years later in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1903 he made a decisive trip to Morocco. Dating from these travels are interesting sketches of urban landscapes and human types.

The following year he made a new trip, this time to Paris, London and the Netherlands, visiting Italy in 1908.

From this point onwards his painting underwent major changes and he took part regularly in the National Exhibitions, achieving great success in those of 1895, 1904, 1908 and 1915, although some of his works were also rejected on the grounds of immorality in 1906, and again in 1910.

After he settled in Madrid, the first decade of the century would be decisive for his work, which was enriched conceptually by his relationship with the foremost intellectuals of Madrid whose company he frequented at the gathering at the Café Nuevo Levante with Valle-Inclán and the one presided by Gómez de la Serna at the Café Pombo, which was attended by the most prestigious writers and artists of the capital.

So began a period of tributes, decorations and appointments during which he also produced interesting works that were shown in various exhibitions in Barcelona, Bilbao and London with a resounding success that culminated in 1922 in the decisive exhibition at the Galería Witcomb in Buenos Aires, where he lived for several months.

Romero de Torres divided his time and work between Madrid and Cordoba, where he was visited by Alfonso XIII.

Around this time he took part as an actor in various films such as La malcasada, made in 1926 and directed by Francisco Gómez Hidalgo, and Julio Romero de Torres, a documentary biography of the master that was completed by Julián Torremocha years after the master’s death.

At the end of 1929, following his success at the Ibero-American Exhibition in Seville, his health worsened and he returned to Cordoba, where he died only months later on 10 May 1930.

There are two essential periods in his painting.

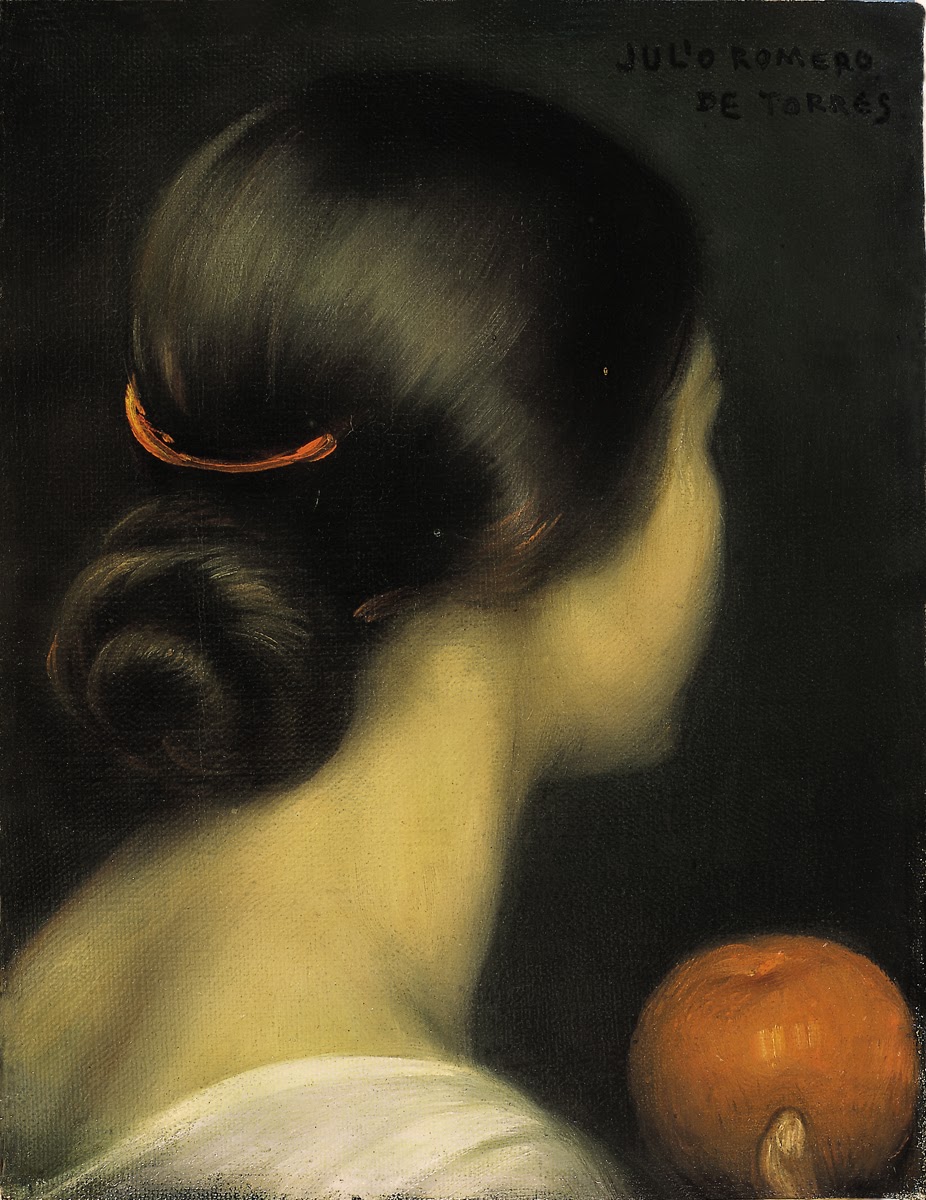

The first spans from his formative years to approximately 1908, when he evolved from the Romantic tradition learned from his father and reflected in Cabeza de árabe (“Head of an Arab”) of 1889 and several Landscapes, and from the influence of the social painting of his brother Raphael as found in Conciencia tranquila (“Clear Conscience”) of 1897, a theme that culminated in 1906 in his controversial paintings of prostitutes entitled Vividoras del amor.

Around 1900 his palette became intensely luminous, as in The Nap, Andalusian Laziness and Bendición Sánchez. He also produced paintings connected with the modern movement such as Horas de angustias (“Hours of Anguish”) and Lectura (“Reading”) – also known as Mujer tendida leyendo un libro (“Reclining Woman Reading a Book”) – which evidence his contact with Catalan painting that is also found in some of his poster designs.

His repertoire also extended to a few genre scenes such as Aceituneras (“Olive Pickers”) of 1904 and religious works such as the decoration of the parish church of Porcuna (Jaen). Lovesick, painted around 1905, is a symbolic allegory of the three ages of women.

The crowning achievements of his first period, executed that year, were the canvases decorating the Circle of Friendship in Cordoba, in the manner of murals, featuring Alegorías de las Artes (“Allegories of the Arts”), a project for which many sketches and photographs are known as models for the final paintings.

These works are influenced, among others, by the American Charles Dana Gibson and his Gibson Girl of about 1890, which inspired the head of one of his women, and by the Belgian sculptor Constantin Meunier whose La glebe, executed in 1892, is reproduced in the Allegory of Sculpture.

The beginning of this second stage in the development of his art was marked by a new concept which has come to be identified with and define his painting.

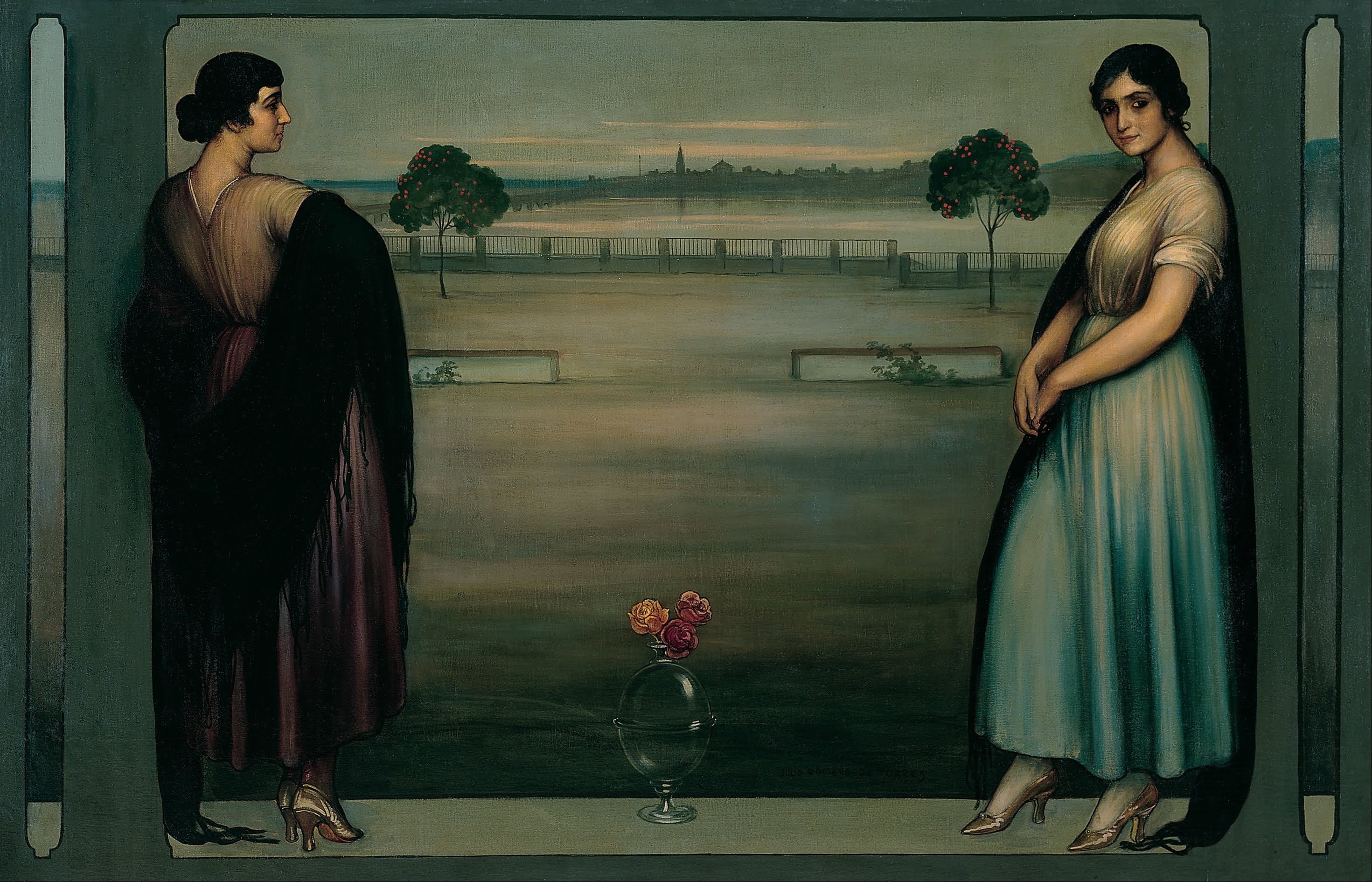

Nuestra Señora de Andalucía (“Our Lady of Andalusia”), Amor sagrado y Amor profane (“Sacred Love and Profane Love”) and Musa gitana (“Gypsy Muse”), executed between 1907-1908, herald later works such as the Retablo del Amor (“Altarpiece of Love”) of 1910.

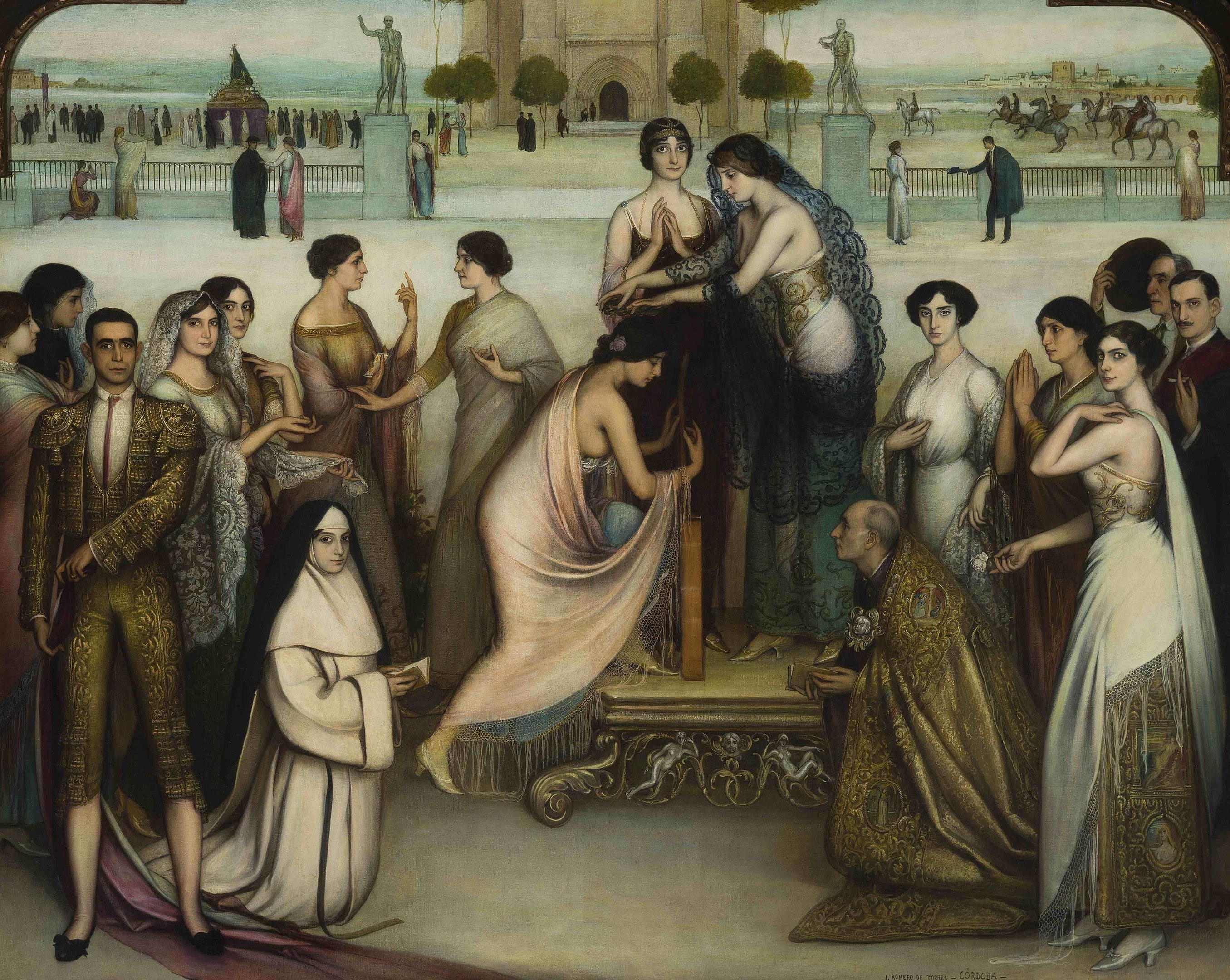

This series of large paintings also featured La consagración de la copla (“The Consecration of the Couplet”), Poema de Córdoba (“Poem of Cordoba”) and La saeta or Cante hondo, painted between 1912-1923.

He produced countless portraits during those years.

Guerrita, Machaquito, Margarita Nelken, Pastora Imperio, Carmen de Burgos (Colombine) and Niña de los Peines are just some of the artistes who sat for the painter on various occasions. There are also portraits of numerous bourgeois ladies of Spain and Buenos Aires, an interest he shared with painting “good girls”, as he called his portraits of many young Cordovan women. The culminating work is Chiquita Piconera, painted in 1930.

His oeuvre in this genre extended to group portraits such as those of the Casana Family and the Basabé Family.

At the same time he also illustrated magazines and books throughout his whole life. Examples of his illustrations are the Cordovan Almanaques del Diario Córdoba and the Feria de mayo and the Madrid Gran Vía and Crónica del Sport; as well as books such as El tiempo de la vida by Manuel Carretero, A la sombra de la Mezquita by his brother-in-law Julio Pellicer, Voces de gesta by his conversation companion and friend Valle-Inclán and, to name just one more, Cante hondo by Manuel Machado.

Poster design was another important field of activity, of which the earliest record is in 1896, when he designed his first poster for the Cordoba Fair, followed by those of 1897, 1902, 1905, 1912, 1913 and 1916; and equally significant commissions were the poster to commemorate the bullfight to raise funds for the victims of the disastrous Battle of Annual in 1921 and the very popular posters he designed between 1924 and 1930 for the Unión Española de Explosivos and for the Cruz Conde wineries.

His poster art remained faithful to the tradition of the greatest contemporary Spanish masters and recalls the Catalan Ramon Casas and a few Sevillian painters.

Two well-defined periods can also be established in these posters: the first, from 1896 to 1905, characterised by the aesthetic of genre scenes and figures with modernist reminiscences; and the second, spanning from 1912 until his death, in which the posters display evident similarities with his paintings.

These two periods are so clearly defined that even the artist’s signature, as in his paintings, is written and structured in two different ways.

He engaged intensively in drawing from his early formative years in Cordoba to 1928, when he was appointed an honorary member of the Union of Spanish Draughtsmen.

This recognition was undoubtedly due to a dedication that dated back to his youth, although this activity is not yet very well known and is therefore rarely mentioned.

He produced drawings in different media – pencil, pen and wash – and on a variety of themes: history, satire, genre, landscape, preparatory studies for his paintings (La gracia, La consagración de la copla, Machaquito como apoteosis del toreo cordobés, etc.) and copies of some of the most important paintings in the Museo del Prado, more than a hundred of which are preserved, chiefly in the Cordoba Museum of Fine Arts and a few others in the Museo Julio Romero de Torres and in various private collections. | Source: © Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga